The Sky is the Limit

Writer Suzy Freeman-Greene Published The Age on 19 April 2008.

One winter’s day, in December 1958, a fluffy squirrel monkey called Gordo was given a helmet and strapped onto a tiny rubber couch. Soon after, he was blasted into space in the nose of an American Jupiter missile. Gordo experienced nine minutes of weightlessness and is thought to have survived his capsule’s re-entry to earth. But the craft landed in the Atlantic Ocean and his body was never found.

Gordo was one of hundreds of animals sent into space from 1949 to 1990. In the name of science, monkeys, dogs, cats, rabbits, mice, rats, frogs, worms, fish, tortoises and even spiders have journeyed towards the stars. While plenty survived, many others died. Space is as an environment without gravity, offering no protection from cosmic radiation. Before humans ventured there, pioneering animals were sent to test these bleak conditions. And over five decades, whether in high-altitude balloons or rockets or space shuttles, they have helped measure the effects of acceleration, vibration, weightlessness, radiation exposure and extremes of pressure and temperature. In America in the 1950s, monkeys were popular subjects for space travel. To minimise their distress, most were anaesthetised during take-off. Russia favoured dogs. As Colin Burgess and Chris Dubbs write in their book Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle, dogs were felt to be closer to humans in their emotional and physical reactions. Pressure chambers, confinement capsules and vibration tables were used to prepare them for their journeys.

The most famous canine cosmonaut was the Russian dog Laika. Wearing a vest and harness, with restraining chains and a sanitation device, she was launched on the Sputnik 2 rocket on November 3, 1957. Amid deafening noise and severe vibrations, her heartbeat peaked at 260 beats a minute. She became the first living creature to orbit the planet. The event was a huge propaganda coup. But for years, Soviet scientists dissembled over one crucial fact. Within the craft, temperatures had escalated. Between five and seven hours after her launch, Laika expired from heat and stress.

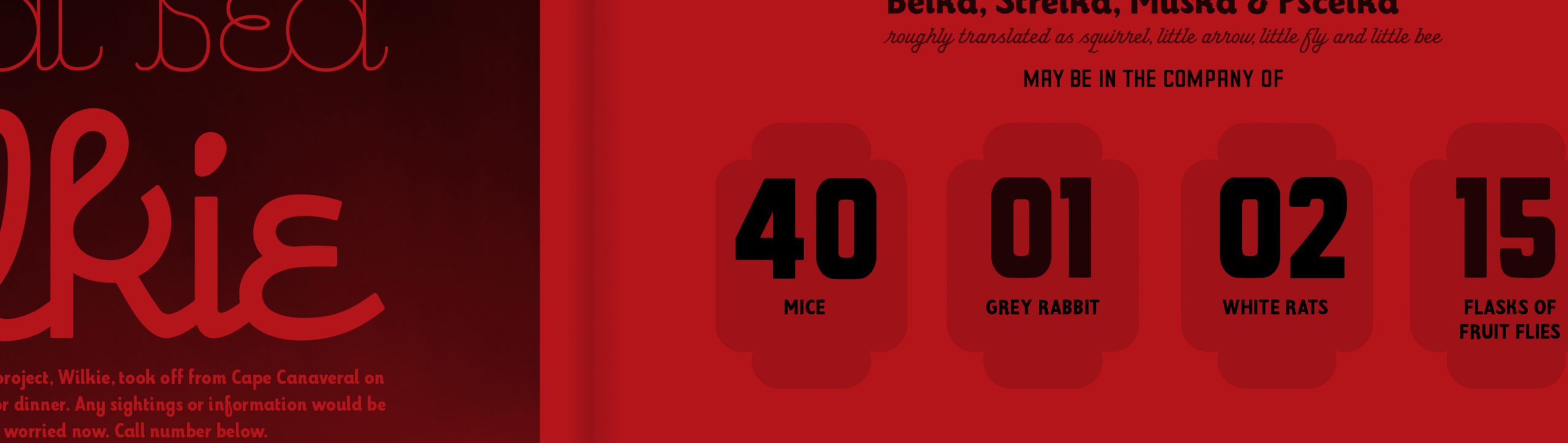

Stephen Banham, a Melbourne graphic designer and artist, was incredibly moved when he read Animals in Space. Banham designs typefaces. He began to create artworks that merged his feelings about those lost creatures with his passion for typography. His exhibition, Orbit Oblique, is a series of illuminated billboards that pay tribute to animals such as Gordo and Laika.

Many billboards take the form of “lost dog” notices. “Desperately Seeking Gordo,” reads one. “Our beloved squirrel monkey.” Though the stories are sad, there are absurd undertones. A posting about Goliath, a monkey whose rocket was destroyed 35 seconds after take-off, ends: “Still slim chance that he may have safely ejected in time. Parents worried.” “I really love the idea of things that are lost,” says Banham. “And that haunting image of the animal in a space capsule is so eerie.” He finds the lost animals’ stories melancholy and blackly funny.

In one case, a Russian dog called Bobik was trained for a mission but escaped at the last minute. So scientists simply grabbed a stray, renamed her ZIB (a Russian acronym for “substitute for missing dog Bobik”) and sent her instead. In America, meanwhile, a chimpanzee called Enos with an unfortunate habit of masturbating non-stop was also sent up in a rocket. During the Cold War, notes Banham, the US and Russia were locked into a highly politicised space race. “These poor unwilling participants were part of this race,” he says.

Banham has deliberately avoided using pictures of animals in his work. He wants his typefaces to express ideas and feelings. All 15 fonts in the show were designed by his studio, Letterbox. One, called Bisque, is making its first public appearance. It’s a slender, slightly ornate script, that somehow feels traditional and modern at the same time. For decades, animals have been vital to medical research, unsentimentally used to test everything from anaesthetics to vaccines to dialysis machines. But there’s something odd about the way so many of these early space travellers were anthropomorphised, even as they proved to be wholly dispensable.

Many were given folksy names: Sam Space jnr (a monkey); Ham (a chimp); Hector (a rat). One American monkey, Miss Baker, was awarded a gold medal on her return from space. Ham, who flew in a capsule on top of a Redstone rocket at speeds of up to 9289 kmh, later appeared on Evel Knievel’s TV show. Yet the pictures in Animals in Space can be disturbing to look at. Many creatures had electrodes implanted in their skulls to measure brain data. In one photo, a hog is strapped to a metal sled, accompanied by a sign that reads “Project Bbq”. In the early 1950s, these hogs were used in crash-simulation tests. After investigative autopsies, the animals were cooked and eaten.

As animal rights protests grew more vigorous, the US finally closed its air force chimpanzee colony in 2002. But Burgess and Dubbs predict animals will continue to play a role in space research. In 2010, for example, 15 mice are due to be launched into low earth orbit. For five weeks, their spinning satellite will simulate levels of gravity on Mars. This test, the authors write, will help pave the way for manned missions to the Red Planet. So even as entrepreneurs talk up space tourism, it seems animals will still go where humans fear to tread.