Monument Interview

Writer Heidi Dokulil Published Monument Magazine in 1997.

Since 1991 Melbourne typographer Stephen Banham has produced seven books and a string of commercial identities which have gained international acclaim and earned his company Letterbox several New York Type Directors Awards, he has developed two typefaces and has a third, Gaberdine, due for release this year. All before he turns 30.

Your work includes publishing, typography and graphic design. Do you find that one medium feeds off another?

Yes very much so. One is influenced by the other which provides a broader idea of what I am doing. Each little section cross-pollinates. In establishing Letterbox I wanted to create a studio time into three sections which include publishing, of my own work or the work of other people, exhibition and teaching and the commercial side of it to keep the money going because the first two things are expensive. So far it has worked out quite well.

What did you do after completing graphic design at RMIT?

I immediately worked for Murdoch for nine months, that’s all I could handle and nine months allowed me the time to save enough money to go to Germany. Right in the middle of my stagy the Berlin wall came down which changed my outlook, as did observing the workings of Meta Design under Erik Spiekermann. He has a much bigger view of where it was all at, it wasn’t just your average graphic design studio. It had a philosophical base. We lived in a flat a block away from the Berlin wall where some amazing images were going up, there was such a big public dialogue. Instead of tuning into the radio or watching television people would go and read what was on the wall and I thought that was a really interesting idea as far as siting information. We produced two posters and glued them up at about six o’clock in the morning. What was really interesting was to sit there as the sun rose watching how the people resounded to the posters, some ignored it and some were a little puzzled and some tried to peel it off as a souvenir. Finally someone came along, took the whole poster down, threw it in the boot of their Mercedes and drove off.

How does Letterbox run?

There are two of us in the studio itself. Flinders Lane is a great place to work because we have a community of various people. There are architects, jewellers, fashion people, textile designers. We all help each other out and get involved in each other’s projects.

Tell me about your collaboration with artists in Melbourne…

At the moment we are involved with an artist-run public art project called Citylights. It is a set of four back-lit signs off Flinders Lane and every one and a half months we collaborate with a new artist visually depicting their work through backlit graphics. The work extends from my own billboard show in Adelaide in 1995. The only trouble was that we had to go to Adelaide and put the billboard up ourselves. So we constructed the pieces in Melbourne in little bits, drove to Adelaide and put it up in 42 degree heat. When we finally put the billboard up a rainstorm came and totally destroyed it. It had a life of about three hours.

Neville Brody’s work has emerged from the UK punk movement, David Carson’s Californian Beach Culture. Do you think your work is influenced by your own surroundings?

I think my work is very influenced by my visual environment, I reference a lot of typography in the found Australian environment and from our culture. I am actually more inspired by artists than I am graphic designers. I tend to like the work of artists who work strong graphic elements – Jake Tilson, Rosalie Gascoyne and Jenny Holzer.

You have said that Australian graphic designers have a lot to say but not a font to say it in … How many fonts have you now developed?

Three. We started with Gingham then moved onto Nylon and we are just finishing Gaberdine. I always say that to produce a font should take at least as long as having a child.

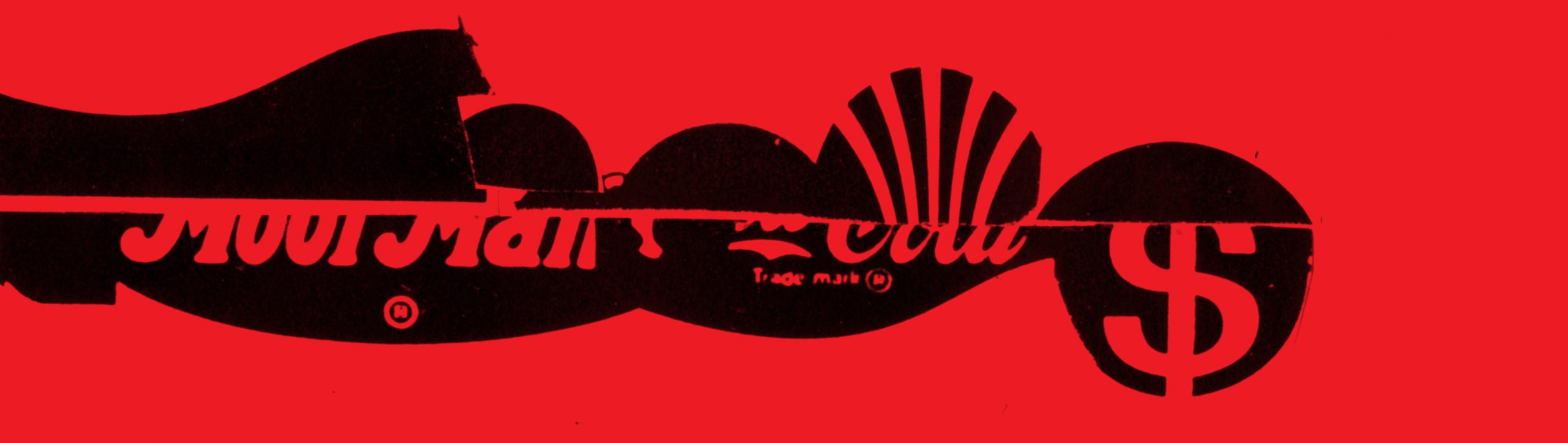

Your work has won a few New York Type Directors Awards – for Qwerty and more recently the corporate identity you developed for OM studios. What was involved with that project?

The OM studios work was a really rare opportunity to be involved with more than just the design of the identity. Their photographic studio is based in a old warehouse which used to be an old outboard marine factory. Over the factory sits a full scale speedboat in silhouette so I suggested that they should name their studios OM as there was already that visual landmark so why reinvent the wheel.

Qwerty was your first series of books, what started that five year project?

Qwerty came about because I started teaching typography at RMIT in 1991 and noticed that a lot of students were totally plagiarising the work of Emigré, Baseline and so forth. So I decided that there was abound to be some really interesting typography in the Australian environment, as we have a totally unique culture which we could reference instead of the filtered graphic design work of other cultures.

Each issue of Qwerty seems to tell story and the six books together have a certain continuity.

There is a sense of continuity both in terms of size and of the common idea of urging the reader to look at type not just as flat two dimensional type set on a page but to look at how it involves us, the forms that it takes and the role of the graphic designer in the wider culture. Even though we are creating something that is often ephemeral we have a responsibility. The Big is Beautiful issue looked at the link between architecture and type and there is a well founded connection. With type’s relationship to language it is linked with virtually everything; as graphic designers we have to understand that what we are dealing with isn’t just a tool to be constantly reconfigured to say the same thing – Buy me! It has a much bigger role and we have a very big responsibility.

Do you think that the design of the page and the linguistic content should work hand in hand?

You can’t separate form and content. A soon as you begin to separate form and content your design will be telling a lie. Whenever I am doing a layout for anything I always read what I am setting because you can’t get a grip on what you are trying to typeset if you can’t understand it. I recently did a piece for Dialogue magazine where I designed the article so that you couldn’t read the article without actually having to physically cut it up and reassemble it. The idea was to urge graphic designers not to just look at the form of image I had done but to be concerned with participating with it. I didn’t really care whether people cut it up or not, it was more that I was trying to prompt the fact that the reader would have to participate in the content.

You had a piece published recently in Name magazine that dealt with the ownership of work.

The idea of ownership fascinates me. At issue was an image I called PAUSE HERE THEN GO. I sourced it from a book for Japanese people to help understand American signage and used it in a show I was having in the public artspace The Word Window in Collins Street, Melbourne. From its original postage stamp size, I blew it up to about seven foot tall. I twas based on the passivity of art. That was in 1993 when David Carson was out here doing lectures in Melbourne and he must have walked up Collins Street at some stage and saw it and took a shot of it. I didn’t know until I was sitting in a big auditorium in Berlin at the Fuse conference watching this amazingly fast-cut film by David Carson and flash!, PAUSE HERE THEN GO, and then flash!, off it went. It was only there for a subliminal moment but it was a very familiar image. I later saw that an entire page of his book End of Print was dedicated to Pause Here Then Go. I couldn’t claim ownership over this image because theoretically the photographer who took the shot should be tapping me on the shoulder. It later appeared in Blueprint magazine, pulled from End of Print. I thought that it was a really interesting thing that I am both the culprit and the victim, in the end the image had a life of its own.

What are you currently working on?

We have just finished our latest font Gaberdine, I will be doing some typography lectures this year, one in Adelaide and one in Hobart. Lots of interesting commercial work and in my head I am slowly putting together other projects. We have been involved in screen-based design and have produced a type-based game on floppy disc called Typotronic. It has been very popular so we are presently producing a CD Rom of that game. Going from print to screen based design was a really exciting departure for someone like me who is so used to tactile media.

Do you have a favourite typographic monument?

To me the best work is work that talks to you and has a sense of humour. I still get very excited when I go past the Sharpies sign in Sydney, it’s type that has a sense of time and place – where it exceeds its role as signage and becomes a cultural landmark. It no longer just becomes a letter or a word but is a signal, not unlike a beautifully designed building.