Eavesdropping + Typography

writer Stephen Banham

I’ve always been a bit of an eavesdropper. And for the people I am with, this can be a little bit annoying. Whether it’s in a café, restaurant or any other social environment, my attention is often split between the conversation right in front of me and the many other tantalising ones happening all around me.

Defined as using ‘surreptitious observation as a technique for sampling the intimate experiences of others’,1 eavesdropping is very appealing — especially the beautiful incompleteness of the communication. When eavesdropping (and especially when one’s attention is divided) what is often heard are fragments of conversations, short clips of a larger discussion. The eavesdropper will often stitch together these parts to create a kind of ‘franken-chat’, a weirdly abstracted (and often factually incorrect) assemblage of information. And that is what makes eavesdropping so playful and speculative – it begs the question ‘what was the entire conversation…?’, ‘in what context would that phrase actually make sense…?’ etc. In tantalising us with some hints, it begs more questions than it answers.

‘Walk & Talk’ eavesdropping is particularly interesting. This is when a conversation is momentarily overheard as the interlocutors briefly walk past. These incidental discussions build slowly on approach then quickly fade. This fleeting moment will invariably capture only a tiny portion of a phrase or sentence, making it even more speculative and compelling. What or who were they discussing? Such conversations happen every moment of every day, and yet are not acknowledged as a rich record of social history. Perhaps in the future, human histories will be traced not just through the familiar voices of the powerful but may also infuse the incidental voices of the everyday – the ‘chatter of the people’.

The informal, unscripted and casual nature of conversation renders it as the petty everyday experience on the periphery – a ‘marginal’ language not to be trusted as a cultural record.

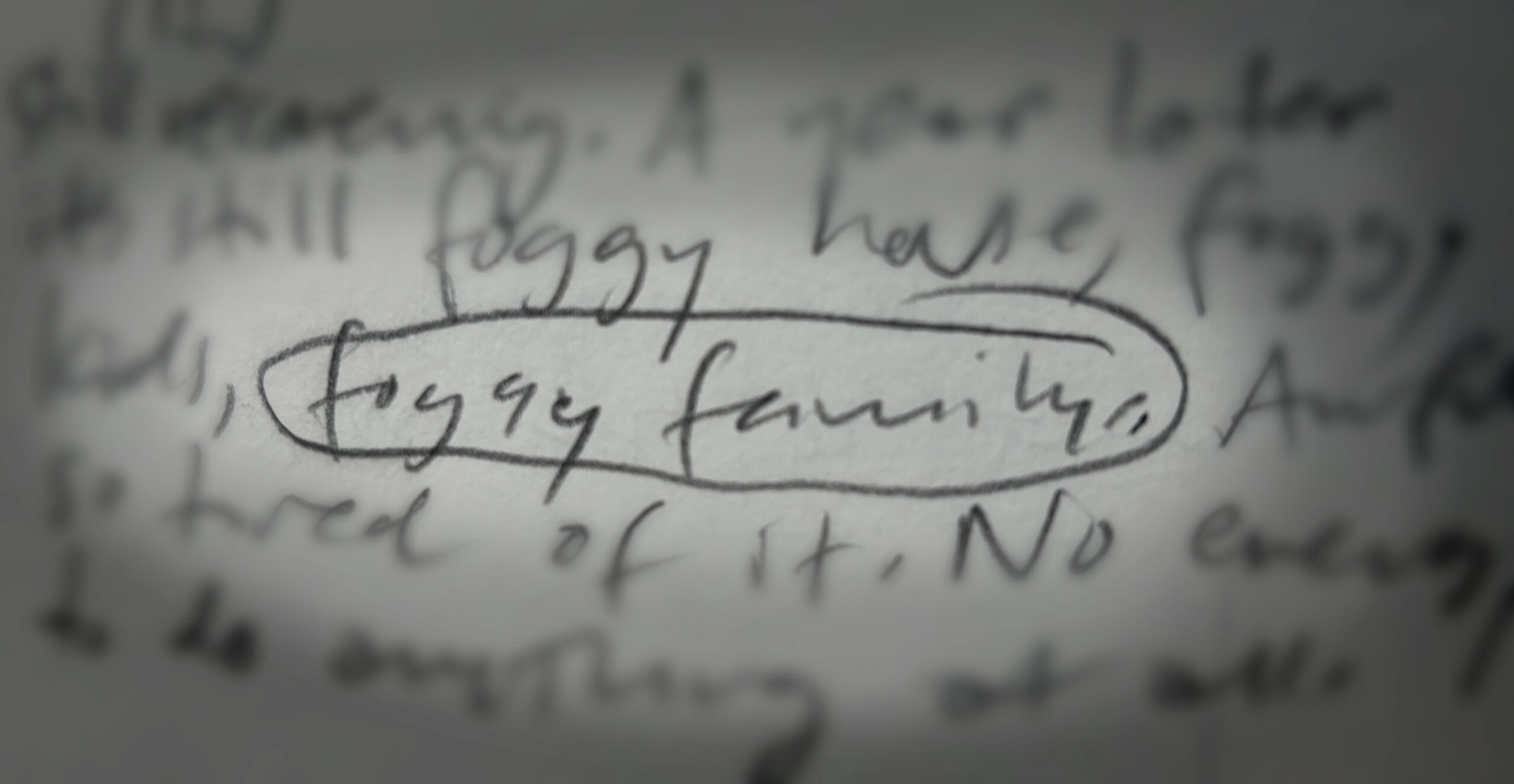

This line of enquiry is the basis of Monument to the Overheard, an artwork installed in Mouclif Park, Prahran, Melbourne. By typographically interpreting snippets of actual overheard conversation2, Monument to the Overheard re-casts these fleeting words and moments in solid powder coated metal, transforming these conversations from ephemeral into the monumental 3, the informal into the formal. The tension between formal history and informal (and forgotten) everyday experience is a familiar one. As a designer predominately working in the glam (Galleries, Libraries, Art, Museums) sector I find myself interacting with archives of many kinds. Whether an archival object is a beautiful old mediaeval manuscript or a bright orange 1970s Black-and-Decker kettle, there is an increasing recognition of the ‘marginalia’, the informal human traces, upon the object. These could be a spontaneous scribble in the margins of an ancient book, or a piece of paper sticky-taped to the underside of a vase etc. Not only does marginalia prove helpful to conservators and scholars in providing hints as to the provenance of an object, but it also tells us something of the broader social context of the object and the human relationship we have with it. Perhaps most importantly, the addition of informal marginalia makes that object completely unique, telling us its ‘uncommon history’ – an alternative story to the formal and familiar historical narrative. A history of the ‘now’.

When writing of marginalia in 1844 author Edgar Allen Poe argued that in making these marks ‘we talk only to ourselves: we therefore talk freshly, boldly, originally, with abandonment, without conceit’. For him the process of writing in the space around a text provides the reader an opportunity for comment ― with no eye for the memorandum book, but having a distinct complexion, deliberately pencilled because the mind of reader wishes to unburden itself of a thought.4

The idea of marginalia is more commonly known that one may think, in fact it’s part of our everyday lexicon – we describe people or issues outside the mainstream as being ‘marginalised’ – that is to say, existing in the outer margins of our attention. Through overhearing (ok, eavesdropping…) upon everyday conversations, Monument to the Overheard presents a ‘typographic marginalia’ – an informal record of the ‘human’ elements that will, in time, encourage passers-by to speculate as to what people from 2023 could have possibly been talking about to use such phrases5 and more importantly what insights this monument could offer in understanding the lived lives of that time. The significance of this is highlighted by the famous street photographer Walker Evans who remarked “Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long”.6

1 Locke, J. Eavesdropping. An Intimate History. Oxford University Press, (2010). P6

2 This primary research involving overhearing conversations from within Prahran Market during March 2023.

3 The closest precedent for this, and indeed much of the inspiration, is the experimental musical sampling by Australian practitioners such as Severed Heads, David Chesworth etc.

4 Taylor, Matthew. Activating (British) Historical Archive Marginalia as a Design Inspiration Resource, Centre for Cultural Ecologies in Art, Design, Architecture. P5.

5 One of the conversational fragments featured refers to the 2020–21 COVID pandemic.

6 Evans, Walker. Thompson, Jerry. 1982. Walker Evans At Work. P 161.